We all know there is a problem with plastics. But just how deep does that problem go?

It is a well known fact that plastic pollution is ending up in the natural environment. We see it everywhere. With no way to fully break down, plastic waste remains, and will continue to remain for hundreds of years. From the depths of the ocean, to the North Pole, plastics and microplastics are being found in animals, water and in the food that we eat.

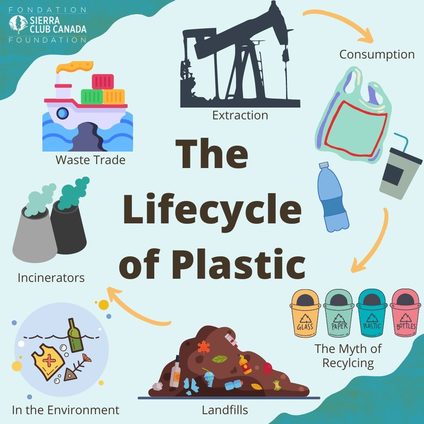

From start to finish, the lifecycle of plastics is problematic. Negatively and disproportionately impacting people of colour, as well as the health and vitality of the environment.

But how and why is this happening?

1. Extraction

The lifecycle of plastics begins with extraction. Plastics are made from raw materials such as natural gas and crude oil. In a simplified explanation, once these materials are extracted from deep within the ground, they are refined into ethane and propane. Next, they are treated in a high heat process called “Cracking” which turns them into ethylene and propylene. These materials are combined together to create different polymers, or plastics. The final step includes another melting process to mold polymer into the desired shape — think of a plastic water bottle or a takeout container.

The extraction of fossil fuels, such as oil and gas, emits toxic air and water pollution to the site’s surroundings — impacting the environment and health for the nearby communities. Most commonly Indigenous, Black and other racialized and/or poor communities. Environmental racism runs deep throughout Canada.

To this day, dozens of Indigenous communities across Canada continue to not have access to clean drinking water — some for decades — due to a lack of proper water quality regulations, erratic and insufficient funding, faulty or substandard infrastructure, and degraded source waters. In fact, source waters for First Nations water supply are increasingly degraded by industrial activities, agricultural run-off, and waste-disposal practices off reserves (Human Rights Watch). Despite making promises to end these drinking water advisory bands, the Federal Government has continued to fail to provide this basic human right to Indigenous communities across Canada.

2. Distribution & Consumption

Next comes the actual use of plastic products — many of which are used just one time before being discarded.

Beginning in the late 1950s, the plastics industry launched a large marketing campaign praising the convenience and ease of plastic. Materials like glass and aluminum were largely replaced by plastic, a cheaper and more durable product. Thus, the culture of single-use plastics was born. From there, the production and use of plastics only grew, continuing to skyrocket in the last 30 years.

- Since 1950, approximately 9.2 billion tons of plastic have been produced. 40% of which comes from single-use products such as shopping bags, cutlery and take-out ware.

- More than 22 million pounds of plastic pollution end up in the Great Lakes every year (Rochester Institute of Technology). Which provides drinking water to over 40 million people.

- There are over 5.25 trillion macro and micro pieces of plastic in our ocean & 46,000 pieces in every square mile of ocean, weighing up to 269,000 tonnes.

- In 2019, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) estimated that $10 billion worth of “virgin” or “primary” plastic is made in Canada each year.

- “Virgin” plastic is plastic directly produced from petrochemicals, containing no recycled materials.

- Canadians dispose of about 3.3 million tonnes of plastic every year, most of which ends up in a landfill or the environment (ECCC)

Virtually every product is coated in plastic now. And in many cases, unnecessarily so. Despite single-use plastics being a relatively new concept, we have become fully reliant on ‘throw-away’ culture. Even for those trying to avoid single-use plastics, it is next to impossible to do so as plastics have been integrated into every part of modern life.

3. The Myth of Recycling

Not long after the introduction of this modern plastic revolution, people started noticing an increase of plastic pollution in their local environments as the United States and Canada shifted to a single-use society. The plastics industry then swooped in with their magical solution: recycling.

Attempting to save its reputation, recycling was positioned as the catch-all solution for plastic pollution. The plastics industry spent millions of dollars sponsoring various advertisements that encouraged the public to recycle. It was framed as a problem (and responsibility) that started and ended with the consumer. If the consumer took the time to recycle, plastic pollution would end. It was as simple as that.

Except that it was a lie. In fact, National Public Radio in the US and PBS Frontline did an investigation into internal industry documents and interviews with top former officials and found that the plastics industry sold the public on the idea of recycling, knowing that it wouldn’t work.

In a 1974 report, an industry insider wrote, “There is serious doubt that [recycling plastic] can ever be made viable on an economic basis." Further, Larry Thomas, the former president of the Society of the Plastics Industry said, “You know, they were not interested in putting any real money or effort into recycling because they wanted to sell virgin material. Nobody that is producing a virgin product wants something to come along that is going to replace it. Produce more virgin material — that's their business."

Despite this knowledge, the industry continued to fund advertisements that encouraged people to recycle, because, as one former top industry insider said, “selling recycling sold plastic, even if it wasn’t true.”

And they were right — it doesn’t work. Of the 3.3 million tonnes of plastic Canadians dispose of each year, around three-quarters go to landfills, a small portion is incinerated and only 9% is recycled (ECCC).

At its core, recycling is a beneficial process. The problem is that it requires advanced technology, energy, and money: “Any material in the world can be recycled — if you separate it, prepare it and pay enough money to put it through the (recycling) process. The question is, is there a market for it? That’s what drives recycling,” says Samantha MacBride, an expert in solid waste management and a professor of urban environmental studies at the Marxe School of Public Affairs at Baruch College of CUNY in New York City. These days, there are over a dozen types of plastics, with some products utilizing multiple different types that would require better sorting technology. Other additives, such as dyes, plasticizers and fire retardants further complicate the separating process. Which means that most plastic that is produced is not recycled.

On top of that, there is little incentive for the industry to support recycling, as the production of virgin plastic is almost always the cheapest option for them.

4. Where does our plastic waste go?

If only about 9% of our plastic waste is recycled — where does it actually go?

Landfills, incinerators and the environment.

Landfills — Majority of plastic waste goes directly to landfills - i.e. a pit or dumping ground for waste. According to CRCResearch, there are over 10,000 landfill sites across Canada.

Incinerators — A portion of our plastic waste is taken to incinerators to be burned. Which as you can imagine, the burning of waste, and often toxic chemicals, has serious impacts on the environment.

The environment — We encounter it every day. Whether you live in the city or the countryside, you will come across plastic waste in the environment. We see it in the news from all across the world, choking wildlife to death and taking over the Ocean.

Another option for our waste, is to send it to the Global South to be dealt with. Historically, this has been a popular method of waste disposal for the Global North to trade it’s waste to countries in the Global South, especially in Southeast Asia, to sort and recycle on their own. In fact, in 2016, it was found that around half of all plastic waste intended for recycling was traded internationally (Science Advances, 2018). China and Hong Kong alone imported around U.S. $81 billion worth of scrap plastic between 1988 and 2016.

Of course, once traded to other countries, the same issues regarding recycling remain. Leaving these communities to deal with the negative impacts of our waste.

In January 2021, a new amendment under the Basel Convention — an international treaty controlling the trade of hazardous waste aimed at curbing the international plastic waste trade — made it nearly impossible to ship plastic waste overseas. Canada did sign this amendment, prohibiting the shipment of plastic waste, except under certain strict conditions. But in October 2021, Canada signed a secretive agreement with the U.S. that allows an unregulated plastic waste trade between the two countries.

Since the U.S. has not signed the Basel Convention, it continues to ship its plastic waste to the Global South — some of which may include Canada’s waste. In other cases, illegal trade markets are popping up, continuing to bring our waste to the Global South.

Today, our plastic waste is still ending up in landfills, incinerators and the environment — just on the other side of the world.

* * *

The plastics issue is a complicated one. At every level it showcases the deep rooted issues of this country and the continued greed of profit over people and the environment.

We cannot be distracted by the lies of the plastic industry and the false-hope of recycling anymore, it is time for real action against plastic. The federal Government has the opportunity to take action, and rules to ban unnecessary and toxic plastics could be finally put in place. After another election, it is time for them to step it up. There is no more room for empty promises.

What is required is a complete shift in the way we use and consume materials. And to move away from mass production and consumption. Until these issues can be addressed, we will continue to see plastic in all corners of the environment. We will not be able to recycle our way out of this problem.